Some Thoughts Upon Leaving D.C.

Look on my works ye mighty, and despair! –Percy Bysshe Shelley, Ozymandias

This week I’m moving away from the D.C. area after spending a good stretch of my adult life living and working here. I’ve had my last beer at the Quarterdeck (I think), and said goodbye to an old friend and hero who gave everything and is now laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery. At this point I’ve been reduced to an old man lurking around the neighborhood and sitting in an empty apartment. There’s simply nothing left to do but wait for tomorrow’s flight, listen to the Saturday opera at the Met (Wagner’s Parsifal), and make an attempt to finish this essay.

The beginning of the end of my time here was 20 January of this year. With the presidential targeting of federal government employees, I decided last spring it was time to put in for retirement. By early summer I had turned in my badge and walked out of the CIA for the last time. A few months later, with the job market hemorrhaging in the D.C. area, my wife and I decided that there wasn’t really anything keeping us here anymore. So we’re now off to Florida.

It’s been an emotional rollercoaster of a year filled with stress-inducing ‘fork in the road’ decisions and transitions. As with anyone facing major life changes, I’ve done a lot of reflecting not only on my own personal journey, but on how D.C. and the country have changed over the course of my time here.

I first touched down in D.C. in 1998 when Bill Clinton was in the White House and the most traumatic event facing the nation was the Monica Lewinsky scandal. My wife (now ex-wife, hang with me, this is a story about change) and I had flown out from Northern California to apartment hunt and take a look at Georgetown University, where I had been accepted into grad school. It was my first time ever on the East Coast. First time anywhere, really.

While I don’t remember anything about the flight, I do remember the taxi drive from Reagan National Airport (then Washington National) into Arlington and taking in all the lush green flora and the stately stone facade bridges that connect the tangled web of roads that snake around the Pentagon and Arlington National Cemetery. I can recall a sense of excitement in entering a new chapter in life and a sense of optimism that came with what felt like a wide-open future.

My wife and I stayed at a cheap, Super-8-style hotel just off Arlington Boulevard. It was recently demolished, no doubt to make way for yet another modern high-rise apartment building similar to the ones that have sprung up like weeds in the now thoroughly gentrified Rosslyn area. That first morning my wife headed off to a job interview while I jumped into a cab to check out the Georgetown campus.

Stepping out of the cab and looking up at Georgetown’s imposing, gothic Healy Hall for the first time I was beside myself. I didn’t really feel like I belonged here. I was a late bloomer, more interested in skateboarding, partying and surfing (in no particular order), in my late teens and early twenties than studying. But somehow, at the last minute, I got my act together, buckled down, turned in my assignments and started to get passing, good, then pretty respectable grades. After a few years of work, I had my undergraduate degree in history.

Then I did something interesting, maybe stupid. At 26 I joined the Marine Corps Reserve. At the time I thought I was going to go for a commission, but six months in Marine Corps Boot Camp and School of Infantry at Camp Pendleton convinced me that I’d probably be better off going to grad school. (I think I made the right call, I likely would have washed out of Officer Candidates School.) After an off-year to work and save some money I applied and was accepted into Georgetown’s National Security Studies graduate program.

That first evening that I was in D.C., I took a very long walk down the National Mall, saw the Vietnam and Lincoln Memorials for the first time, and passed one Smithsonian museum after another–American History, Natural History, National Archives–until it grew dark. For someone who had grown up in Bay Area suburbia and had never left the country, D.C. was a fountain of urbanity, history, culture and knowledge and I was ready to drink from it.

We put down a deposit on a tiny studio apartment in a modest brick building in a little neighborhood just above the Marine Corps Memorial and flew back to the west coast. That summer we drove across the country in my little Mazda pickup truck. Other than a mattress to sleep on in our first week in the apartment, we brought no furniture. We’d eventually pick-up some second-hand pieces in Washington we figured. As it turned out, we were so poor for the next two years that the majority of usable furniture we acquired were pieces abandoned in the parking lot by former tenants.

I spent those two years cloistered in that apartment writing papers and going to class in the evenings. But I loved D.C. and Georgetown. I had an unrealistic dream of becoming a professor and never leaving the campus. But this was never really in the cards. My wife got pregnant during my last year of studies. Pursuing a PhD, even if I could get into a program, would mean several more years of living around the poverty line. My wife had carried the financial burden while I was in school. It was time for me to find a job.

Following my graduation, my wife took a tech job on the West Coast and we moved back to the Bay Area for about a year. Then 9/11 hit and my Marine Corps Reserve unit was activated. Back at Camp Pendleton, I applied to the CIA and started moving through the interview process. But before I could start my career a war loomed. After a year of training my unit was attached to the First Marine Division for the invasion of Iraq.

I survived my bit of the war, coming out with a bit of mental trauma but otherwise unscathed. Within a month of being honorably discharged from the Marines I had moved back to Northern Virginia and started my first day on the job at the CIA.

I would spend over twenty years with the Agency. It was a challenging and exciting career. I can’t really get into the details of what I did. But I can say that I had the honor of working with some of the best, most dedicated professionals in the country. To see them maligned by politicians as some kind of non-existent ‘deep state’ was a slap in the face.

I saw this change of tone accelerating in the later part of my career as the War on Terror wound down and the country’s politics radicalized. As this unfolded, the whole basis of my work changed as well.

When I came into government service, there was an unwritten code between those who serve in the Intelligence Community (IC) and their political overseers. This code stemmed from a framework of rules, laws and norms: the oath to the Constitution that one takes on the first day of the job, the Hatch Act, which forbids government employees from engaging in overt political activity, and myriad other contractural agreements to protect classified information.

The intelligence officer is asked to operate in morally ambiguous areas, perhaps even take personal risks, while maintaining their personal integrity and duty to work within the confines of the law.

By the same token, the intelligence officer serves politicians who must maintain their legitimacy by not abusing their power to use the IC for domestic political purposes and, overall, adhering to the same oath to the Constitution and rule of law that applies to everyone in the government.

An administration that operates with contempt for the law, or which injects politics into agencies that strive to maintain political neutrality and analytical objectivity, breaches this contract and subverts a system that, although most Americans don’t see it, works to preserve their security.

I watched as the Trump administration breached this code time and again. There was the well-documented endemic financial corruption. The federal probe into Russia’s interference in the 2016 elections, which brought charges and convictions of tax fraud, lying to Congress and investigators, obstruction of justice, witness tampering and campaign violations for a wide array of Trump administration officials. An investigation by the Office of Special Council in 2020 named 13 senior members of the Trump Administration who violated the Hatch Act during the 2020 election.

Then there were the big ones: Trump’s illegal scheme to withhold congressionally mandated funding for Ukraine in order to pressure Ukrainian President Volodymir Zelinsky’s government into a public investigation of the Bidens, which led to Trump’s first impeachment. And, crescendo-like, arguably one of the greatest crimes in our nation’s history: Trump’s attempt to steal the free-and-fair presidential election of 2020, of which I’ve written several times on this page, since I believe that this event is pivotal to the crisis we face today.

To me, it appeared as though Trump was assaulting the entire basis for ethical, law-based government. How can public service work if whistle blowers who call out possible violations of the law are targeted for retribution and government workers are smeared en-masse as so-called ‘deep state’ members in retaliation?

At some point during the first Trump administration, I realized that I had become far more worried about the plight of American democracy itself than foreign threats such as China, Russia or ISIS. Americans, if united, can deal with threats from abroad, but if our democracy is corroding from within, what’s the point of manning the ramparts?

Through all of this I limped along, growing older and dealing with a wave of mid-life problems and crises. A rocky career path ended in a dead end. Then, in a one-two punch, covid hit and my long-struggling marriage collapsed. Rock bottom, homeless and drunk, I watched the 6 January 2021 assault on the Capitol from a depressing Extended Stay America hotel room.

As often happens in life if you just hang on and refuse to give up, things get better. For me this occurred when I met my current wife Kate, fell head-over-heels in love, and felt an overwhelming desire to re-build my life. Kate and I both had wonderful children, and I wanted to watch them grow and be there to support them. I resolved to push on at work for a few more years because, at the end of the day, despite all the frustrations, it meant a lot to me. I couldn’t imagine doing anything else.

Then Trump got re-elected.

In a twist of fate, Kate and I had decided to move from the suburbs of Fairfax closer into D.C., just before DOGE’s assault on the federal workforce got underway in full. We had committed to sticking around the D.C. area just when the rationale for doing so was rapidly unwinding.

It was Elon Musk’s ‘five accomplishments’ emails that broke the camel’s back for me. I had seen weeks of demonization, intimidation and illegal firings of federal workers. Now I was undergoing stressful weekends facing the possibility of being forced to resign on Monday mornings on principle rather than put my signature on a document that went outside of my chain of command. I decided that it was time to retire.

Ironically, we had moved into an apartment that happened to be in the same Arlington neighborhood that I had lived in while attending grad school twenty-five years prior, just above the Marine Corps Memorial. I couldn’t escape the feeling of having come full circle.

But Washington felt totally different now. The monuments downtown hadn’t changed, with the exception of new editions, (the World War II memorial was completed in 2004, the stirring Martin Luther King monument in 2011). As usual, the buses still disgorge mobs of tourists and school groups, many with patriotic attire, to pay homage to our nation’s most revered monuments.

But these monuments, and the buildings, statues and plaques proclaiming the greatness of American liberty and democracy, once such a source of pride for me, now give off a slightly hollow aura. Rather than our nation’s past achievements and struggles, they speak more to me of my generation’s failure to uphold the very democratic principles that previous generations fought and died for.

Upon returning to the old neighborhood, I eagerly resumed my old workout of running across the Arlington Memorial Bridge and around the Lincoln Memorial Reflecting Pool (in my twenties I’d circle the Washington Monument, but those days are long gone). It’s a world-class, scenic run, right in my backyard. But soon I was met with the disturbing sight of National Guard troops patrolling the Mall.

On weekends Kate and I head downtown, to go to a museum and have lunch and drinks. Again, we see National Guard troops with M4 assault-rifles, similar to what I carried in Baghdad, patrolling the streets. Banners of Trump with that ridiculous, menacing scowl, now hang, unabashedly authoritarian-style, over the facades of several federal buildings. I can’t be alone in wondering if this is the new normal in D.C.; In America?

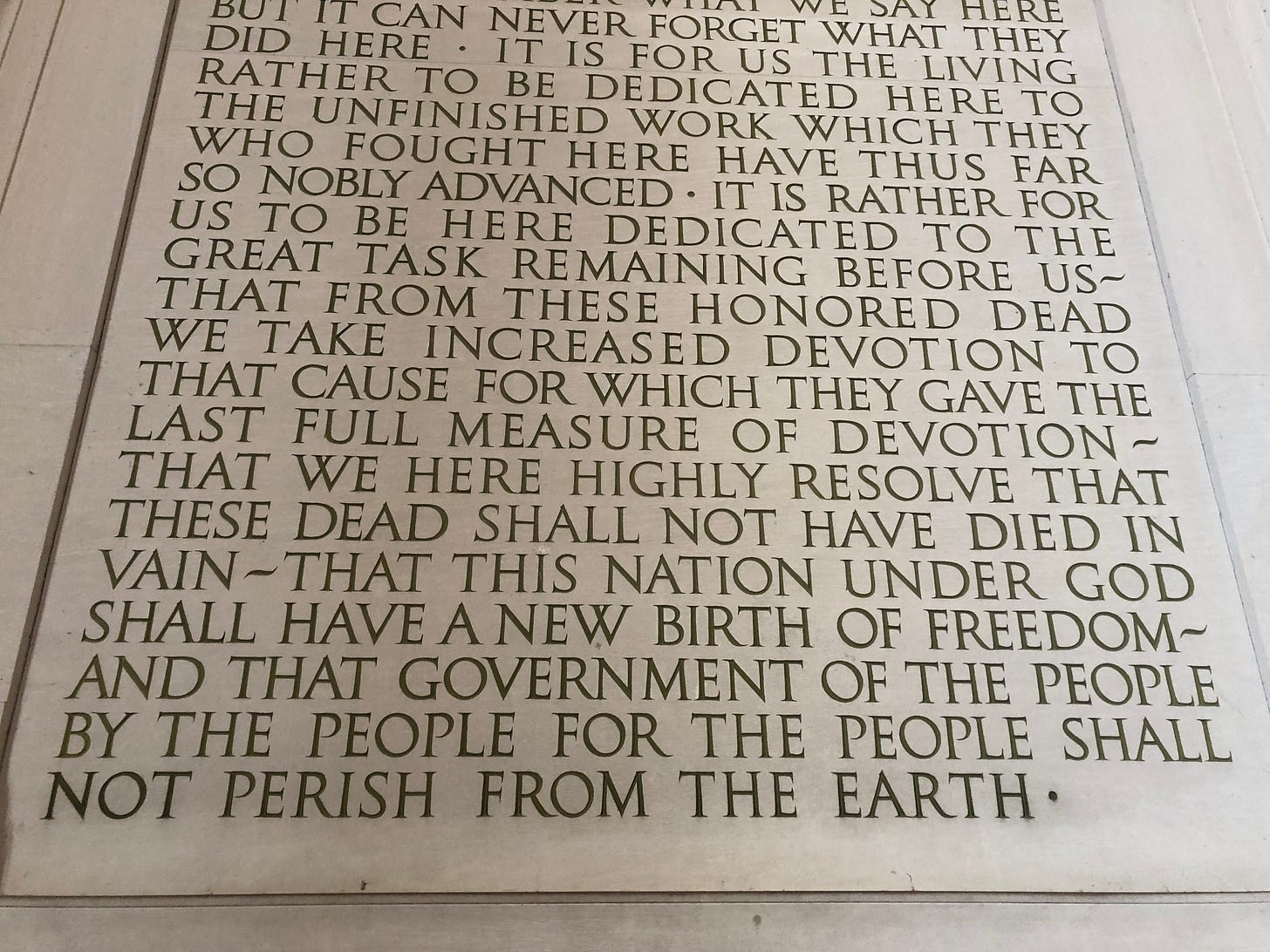

On the National Mall, people from all over the country and the world still stroll down the paths along the reflecting pool, taking in the monuments. Regardless of the world’s troubles, I always took solace from this place, from the sight of people from all walks of life seeing the Mall’s display of our core values, the true source of America’s greatness. But these monuments are really just concrete, re-bar and marble. They won’t mean a thing if government for the people, by the people, perishes in America.

Nineteen years ago the late Charles Krauthammer wrote that the true power of Washington D.C. lies in the words and “the power and glory of ideas” rather than base displays of power. Jefferson’s “words on religious freedom, inalienable rights and sacred honor” and Lincoln’s Second Inaugural and Gettysburg addresses, which are inscribed in the walls at the Lincoln Memorial, are why we fought the wars now memorialized on the Mall.

“Other capitals celebrate the gloria and fortuna of victory. No Arch of Triumph here”, he wrote. I wonder what Krauthammer, who passed away in 2018, would make of Trump’s plans to build an ‘Arch de Trump’ just across from the Lincoln Memorial.

Krauthammer wrote the above before the dedication of the Martin Luther King monument. So I’ll end by adding one inscription from that monument from King himself: “We shall overcome because the arch of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

I’m clinging on to Dr. King’s words as I start this new phase in life. I’ll be in Florida, but I’m going to keep doing whatever I can to defend our democracy, however modest. Here’s to new beginnings. Here’s to never giving up the fight. It’s a fight worth having. You’ll be hearing from me.